Earthquakes, eruptions of Vesuvius, plagues, garbage crisis, bloody Camorra wars: in Naples, all the natural and man-made disasters over the centuries take on the character of essential events. Here, a metaphorical leap takes the truth of facts beyond reality. It is as if the city’s anthropological identity were built on a need for inevitable breakdown, collapse and disintegration. Nothing truly ends or begins. Everything returns. And so the stubbornly beautiful remains intertwined with the irremediably ugly, the good with the bad, the just with the unjust. We shall tell this long story like a numeration of infinite sorrows, but we know that no one will ever be able to separate it from the rhetorical counterpoint of mythical beauty, condemned to oleographic repetition.

There is something specific about the tragedies of Naples: they seem to be affronts to beauty and also, contrarily, threatening and astonishing propagators of a dangerous and deadly idea of beauty. Not of fragility or superficiality, but of a finitude of beauty that entices because, in its awareness of its own vitality, it is naturally disposed to dying. As in some lugubrious pagan festival, even the dreadful garbage crisis, the filth that devours the rich and glimmering beau monde of the Neapolitan landscape, reproposes the city’s most ancient and most modern image: a city that sees in its own death, in its own dying body, the extreme brilliance of beauty.

At this point one needs to give voice to an idea that seems to come from the heart of Naples, from its dark foundation as a city consecrated to catastrophe; our image is one of a city that crucifies itself, the city that Antonio Biasiucci, Doriana and Massimilano Fuksas, Mimmo Paladino and Tony Servillo have chosen as their stage. For the cross is art history’s most beloved sign, rooted in the city’s tradition and popular attitudes – a sign that unites earth and heaven, death that indicates resurrection, suffering that is joy.

The stage is the Church of Donnaregina Vecchia. The architecture of Fuksas, like a gigantic Oldenburgian icon, rises laboriously amid joints, nails and props that hold it in precarious equilibrium. It comes from a forest of tree trunks around the altar, the point of arrival of the via crucis Mimmo Paladino has engraved in iron and on paper; figures abandoned on the floor or suspended and wandering from the vaults act as a chorus to the voice of Tony Servillo, who tells about the city through its numbers. In the small side chapel Antonio Biasiucci’s images describe the Naples of ex votos, a pause for meditation for the visitor, an invitation to concentrate the glance and to think about art as a gesture that is offered out of excess, a creation and narration of an idea and not a mirror of reality, neither support or denunciation.

Napoli in croce (Napoli crucifixed) is a way to understand Naples in real time, recording the catastrophe live, but with eyes wide open to the vastness of history. We cannot do without beauty, we cannot do without Naples, we cannot do without modern language and thinking.

Mimmo Paladino

Memory and quotation, figurative mimesis and a fantastical recreation of reality. Mimmo Paladino’s art sinks into the unconscious of Mediterranean culture, to capture its symbols and legends, left buried beneath the veil of Reason that reduces the world to profits and losses, saints and sinners. His stylized heroes and Don Quixote are mythic simulacra of a nocturnal universe that moves behind, in front of and beyond the usual evident and reassuring social identities. They tell a story – both ancient and current, fictitious and real – that restores a sense of the wealth of human reality’s complexity.

Massimiliano and Doriana Fucksas

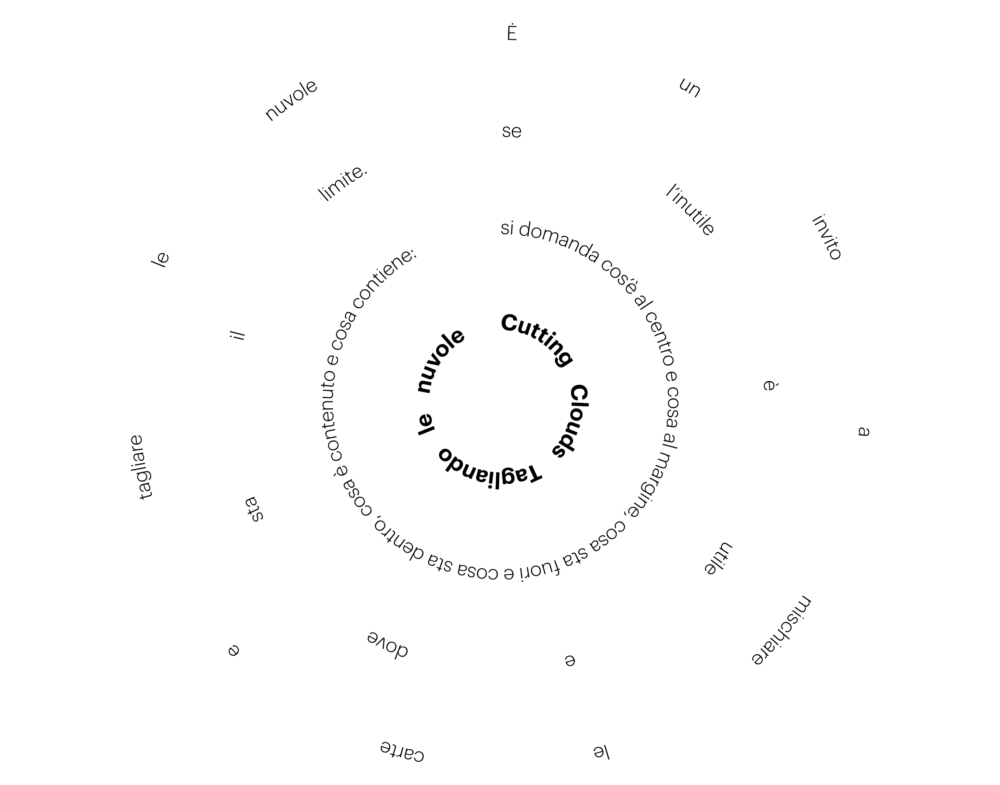

The architecture of Massimiliano and Doriana Fucksas is the result of a concise confrontation between two identities whose reciprocal diversity has created a point of strength and communion. They are the spoils of a conversation that has taken place between sleeping and waking: when time disappears, condensing into a continuous succession of images that is thought. This gives rise to three-dimensional objects with vague shapes like clouds, or free like sails, which, once translated into signs and plans, finally become livable, habitable spaces, traversable by indefinite crowds, delineating a new experience of the city.

Antonio Biasiucci

All shades of white and black, the mystery of back-lighting and the luminescence of the smallest details captured within total blackness, are the tools Antonio Biasiucci uses to invite us on a voyage within the object and its perception. He searches for novel visions and new perspectives that are capable of giving things meaning, opening them up to the imagination. And so the photographic reproduction of reality becomes a recreation of reality, since the eye does not see objects, but figures of things that signify something else and convey a realm beyond.

Toni Servillo

Similar to what happens to human reality in the passage from waking to sleeping, an actor enters and exits the role he or she is playing. In this creative transformation of his own identity and the identity of his image, Toni Servillo gives voice and body to a depth of feelings, dreams and hopes that, invisible, resist beneath the violence of the present or the armor of everyday indifference. It is a reality that awaits only the opportunity to rebel from its fate as a puppet, but which at the same time knows that it is not sufficient to rebel, but rather to know that one is rebelling.