Joseph Beuys was one of the most emblematic artists of the second half of the twentieth century. His research took him along new paths, indissolubly fusing his life with his being as an artist in a radical overlap between art and life. Hence we have to start from his biography to understand his work. During World War II he was a pilot in the German air force. He was taking part in the Nazi offensive against the Soviet Union when his plane was shot down. He was found badly injured and suffering from frostbite by a group of nomadic Tatars who healed him by wrapping him in fat and felt. He survived and ended up in a British prison camp.

From this experience Beuys drew motifs of inspiration that accompanied him throughout all his work, following a mysterious thread of shamanic spiritual rebirth by which mankind attains the final harmony in itself and with nature.

After the war he studied art at the Academy in Düsseldorf, where in the early 1960s he became a lecturer and was then dismissed in 1972 after organizing a strike. Meanwhile he had become one of the most active members of Fluxus, a group that brought together a large number of artists in Europe as well as in America, who shared the desire to explore the significance of art in relation to its social functions. Hence Beuys’s famous motto, “everyone is an artist,” which reaffirms the concept of total art, ranging from the purely aesthetic experience to everyday events.

Beuys’s work consists mainly of actions and happenings. In the United States he met Andy Warhol, an artist in many ways his direct opposite. Warhol was the most important representative of American Pop Art, but the relation between the two artists is an important key to understanding the ideological basis of post-war art and appreciating the differences that existed at the time between American and European art. While American Pop Art retained a celebratory and upbeat approach to contemporary life, developments in contemporary European art, of which Beuys became a symbol, were characterized by a more problematic and complex relation with the crisis of European intellectual consciousness, stemming from the burden of an overwhelming tradition shot through with light and shadow. The art-life relation that stemmed from Beuys’s Soziale Plastik subverted any conception of art that assumed an anthropological value and as such it addressed the whole arc of human activity, from science to politics, in particular exploring the practical dimension of action. This comprehensive conception of art makes humanity responsible for its every act, requiring it to be involved and committed so as to act creatively.

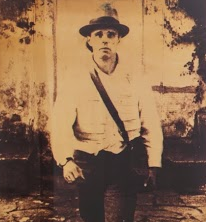

Criticality, responsibility, freedom, self-determination, participation, equality and democracy, are the corner-stones of Beuys’s work. These ideas are all summed up in the motto La Rivoluzione Siamo Noi (“We are the Revolution”) on the poster published for his first exhibition in Italy, presented in Naples in 1971 by Lucio Amelio, who also organized the legendary meeting in the city between Beuys and Warhol. The photo was taken in the drive of Villa Orlandi in Anacapri, where Pasquale Trisorio and his family hosted artists and intellectuals from many countries all through the 1970s and 80s. It is one of the most significant posters of the 1970s. La Rivoluzione Siamo Noi is representative of Beuys’s political aesthetic while also underscoring the relevance of the message in our own time, following the collapse of the great collective ideologies. The slogan of the artist is bound up with the conception that even our commonest gestures embody a magic act, a matter of art as our very lives. La Rivoluzione Siamo Noi is present at the Madre in a double version, which emphasizes the emblematic and open nature of the work, and its message: a one-off image dedicated by the artist to Villa Orlandi and the first print of the edition, a mirror copy of the original.

EV