Madre Museum presents Ugo Marano. The Rooms of Utopia, curated by Stefania Zuliani and Antonello Tolve.

The exhibition, also strongly supported by the President of the Campania Region Vincenzo De Luca, features more than forty works, including one – Papa non c’è (1987) – that has never been exhibited outside the Capriglia home-studio: sculptures, installations, drawings, paintings and artist’s books from the late 1960s to 2010 give life to a true narrative of Marano’s work, declined through the guidelines that have oriented his activity. A path of art and thought that has recognized utopia as its strength and motive, not structured in chronological order nor according to a selection by techniques and subject matter, but articulated in seven sections, in seven ideas of Home, Body, Time, Art, Writing, Nature, and Bond.

Ugo Marano’s work testifies to a close bond with nature, the very matrix of his artistic action, whose metamorphic energy is not represented as it is, but translated and restored in its vitality. There is no privileged technique for this translation of energy, for putting it into concept and thus into form of the continuous natural metamorphosis. In 1969, for example, Marano chose ceramics (arte regina) to recreate the unstable horizon of the sea, giving birth to the first anti-pavement, and many times over the years he has continued to entrust ceramics with his marine narrative: the musical sequence of Waves (1981) exhibited here is clear evidence of this.

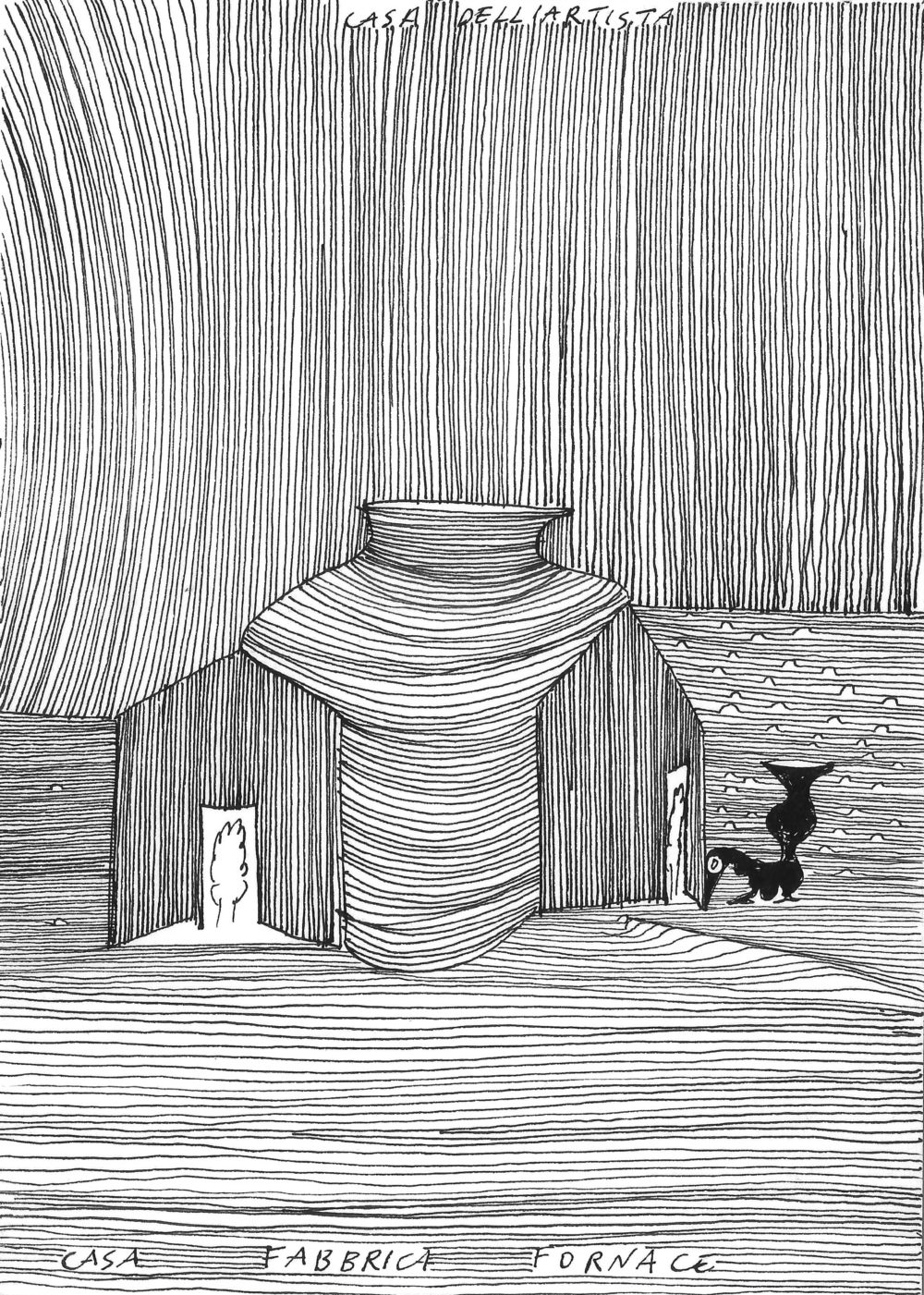

Ceramics also becomes evidence of the artist’s relationship with the territory and with some elements of its tradition: in fact, there are recurring works that refer to the experience of the Vasai di Cetara and Rufoli, a land of fine clays where the firing of terracotta is an art and a collective rite, as recounted by the Museo Città Creativa in Ogliara, which had its inspirer precisely in Marano. On display are some works that refer to his research conducted on the vase, part of a much larger series that the artist made in the early 2000s.

Another recurring element, clearly recognizable in the exhibition itinerary, is the chair, an emblem of a vision of art that does not tend to obtain an easy result but to ceaselessly elaborate new strategies of life and thought: and after all, “reckoning with ideas is done from an uncomfortable chair. Armchairs make ideas soft: it is the deception of the chair.”

Writing, the sign that becomes drawing and word on the blank page or on the surface of the work, accompanies Ugo Marano’s entire journey. The exercise of writing has at least a twofold value for the artist, representing both the moment of analysis of the reasons and procedures that lead to the work and the space of a free, playful, sometimes ironic but always poetic invention. Two moments that are not mutually exclusive and that often coexist in the same text: the artist’s writings, it was Filiberto Menna who emphasized this when presenting Marano’s work at the Schneider Gallery in Rome in 1972, certainly offer “the key to a deeper understanding of the drawings and sculptures,” but they also open to broader horizons of meaning, creating visionary scenarios or returning traces of encounters and life experiences.

Whether it develops in the often square and minute pages of the many books made in artisanal and deliberately poor editions, photocopied and carefully folded sheets where the cover is sometimes followed by a page of love and not typographic respect, or whether it patiently carves itself into the material, as happens in the work Papa non c’è (1987), an embrace of words and humble earth that still welcomes visitors to the Capriglia studio house, writing is for Marano the occasion of a necessary dialogue.

In his secluded proceeding, Ugo Marano’s research has never renounced the sharing of experience and thought. Over the years, his two houses have been crossroads of encounters and factories of connections, building sites of ideas that have constructed ties, connections, participation. Psicocesso (1978), made in the large spaces of the Capriglia studio is, in this sense, an exemplary work. It is a relational device that together with the artist has tested numerous but always chosen participants (among others, Tomaso Binga and Filiberto Menna) called to put themselves on the line in a moment that has always been private: a challenge, a forcing that breaks the mould and forces a risky communion. To those who approach his work, Marano demands an assumption of responsibility, proposing a work of slow stitching and simultaneously an effort of conjunction of which Ego strumento is both image and result, even manifest, thanks to the reflections that are wrapped around it in sinuous writing.