The artistic path of Mario Martone (Naples, 1959) – which is based on performances, theater, cinema, opera, creation of theatrical groups and spaces – formed over time as an “archipelago” in which the works, distant in time, space and form, find themselves in a mutual dialogue.

The first performance of the Falso Movimento group, founded by Martone in Naples in 1979, took place inside the Neapolitan gallery of Lucio Amelio. The upcoming film by Martone, which will be presented in the autumn of 2018, titled Capri-Revolution, is inspired by an artwork that the German artist Joseph Beuys produced in 1971 in Anacapri, We Are the Revolution. Beuys’ relationship with the island of Capri will deepen in 1985, when the artist realizes with Amelio the artwork Capri-Batterie (a yellow light bulb that ideally takes energy from a lemon), that inspired the provisory title of Martone’s upcoming film. This scenario is evoked at the entrance of this exhibition by the image of a forest taken from a sequence of the film (photo by Mario Spada) and by some props. It is no coincidence that the Madre · museo d’arte contemporanea Donnaregina of Naples presents the first retrospective exhibition dedicated to Mario Martone. Welcoming the Fluxus tension that animates his research, the exhibition is conceived as a film-flow based on the study of the materials stored in Mario Martone’s archive, created with the executive production of PAV, Rome, and with the support of the Fondazione Campania dei Festival – Napoli Teatro Festival Italia.

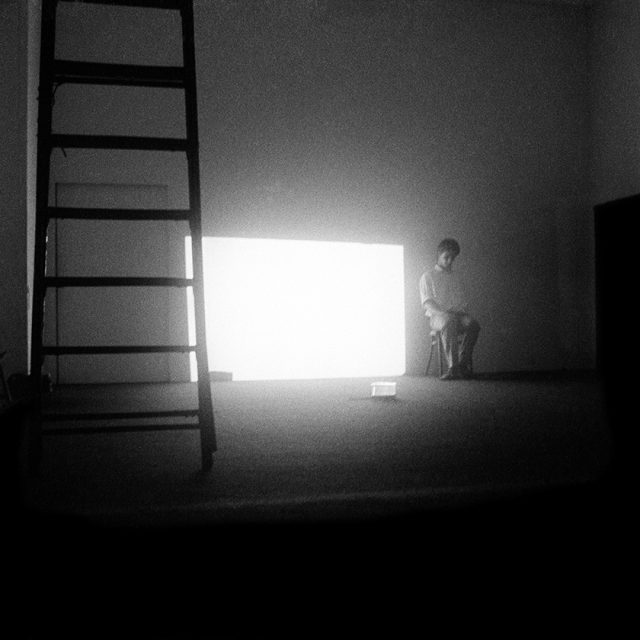

Through the editing of unreleased documents and films, archival footages, film cuts and takes of theatrical performances that document the multifaceted creative activity over a period of forty years, Martone’s artistic experience is presented according to an evocative and non-chronological order, in which all the elements that tell about the story of the director coexist in a horizontal relationship that is contemporary in itself. Projected simultaneously on four screens in the Re_PUBBLICA MADRE Gallery, the film-flow reelaborates the “mise-en-scène” of a theatrical performance realized by Martone in 1986, Ritorno ad Alphaville, inspired by Jean-Luc Godard’s film, recreating its circular trend and the simultaneous vision by the public.

Martone began his activity in Naples in 1977, in the avantgardes context of that period. Here, in 1979, he founded the Falso Movimento group and created shows that combine the elements of theater, cinema, music and visual arts, such as Segni di vita (1979), Tango Glaciale (1982), Il desiderio preso per la coda (from Picasso 1985), Ritorno ad Alphaville (1986), all presented in extensive international tours. In 1987 Martone proposed to Toni Servillo (Teatro Studio di Caserta) and Antonio Neiwiller (Teatro dei Mutamenti) to disband their respective theatrical groups to form a new collective, called Teatri Uniti. The old and the new companions shared his open and collaborative attitude: within a few years the productions of Teatri Uniti involved many other artists, among which Fabrizia Ramondino, Leo De Berardinis, Enzo Moscato, Carlo Cecchi and Steve Lacy. Martone imagined that the research of the group could have been expanded to include cinema. He realized his first films, Morte di un matematico napoletano, winner of the Grand Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival in 1992, L’Amore molesto (1995, based on Elena Ferrante’s debut novel) and Teatro di guerra (1998). The same attitude animated the direction of the Teatro di Roma, assigned to Martone from 1998 to 2000, embodying a radical change in the programme, involving also other arts and new scenic expressions. He founded a theater, the Teatro India, obtained from a disused factory on the Lungotevere.

Martone experimented also different formats, realizing in 1993 the documentary dedicated to the Neapolitan gallerist Lucio Amelio and his project Terrae Motus, in 1996 the mediumlength feature film Una storia Saharawi, made in the Saharawi refugee camps, and filming some theatrical works, including the Teatri Uniti performance-manifesto titled Rasoi (staged with Toni Servillo in 1991 and then turned into a film in 1993). As a theater director he staged several Greek tragedies (including Edipo re and Edipo a Colono, with a choir of immigrants and the scenography by Mimmo Paladino) and several texts by contemporary authors. Starting from 2000, he directs grand operas in major opera houses around the world: among the most recent, Andrea Chénier by Umberto Giordano, which inaugurated on December 7th, 2017, the opera season of the Teatro alla Scala in Milan. A few months later he staged Giuseppe Verdi’s Falstaff at the Berlin Staatsoper with the conduction of Daniel Barenboim.

In recent years, he worked on the making of two films that deal, through a contemporary look, with the history of the nineteenth-Century Italy: Noi credevamo (2010) and Il giovane favoloso (2014), awarded with twelve David di Donatello. During his direction of the Teatro Stabile di Torino (2007-2017), Martone staged the Operette Morali by Giacomo Leopardi, La serata a Colono by Elsa Morante, Carmen by Enzo Moscato with the Orchestra of Piazza Vittorio, Morte di Danton by Georg Büchner, Il sindaco del rione Sanità by Eduardo De Filippo, realized in the suburbs of Naples with the actors of the Nest of San Giovanni a Teduccio.

As in the entire artistic research of Mario Martone, in this retrospective exhibition at the Madre museum the active role of the audience is crucial. In the middle of the Re_PUBBLICA MADRE Gallery there are thirty-six swivel chairs placed on a platform, each one connected to a headset which has direct access to the four audio channels and corresponds to the timing of the four screens on which the film-flow is projected.

By turning his chair, the spectator will be able to direct his attention alternatively to the flow of the film on the four screens and perceive both the individual images on each one and the possible visual or thematic connections between them. The film itself is edited according to a constant flow that contains both the two-dimensional surface of the screen and the three-dimensional space of the screening environment. The internal connections are visually and sensorially presented just as the circularity of both the work and the artistic research of the Neapolitan director.