The Madre museum in Naples is the only Italian venue of the first midcareer retrospective devoted to Roberto Cuoghi (Modena, 1973), one of the most enigmatic, mysterious and fascinating Italian artists of his generation. Cuoghi’s artistic practice brings together the sculptural and compositional qualities of the visual arts and the scenic-narrative qualities of a performer and storyteller. His unique paintings, sculptures, photographs, installations, videos and films, sound works and performances use partly unconventional techniques and materials, which the artist often experiments with and even reinvents. They explore the notions of the simulacrum and the symbol, memory and immanence, devotion and superstition, transformation and metamorphosis (of the body, identity, language and the forms themselves of representation and expression). There are references to antiquity and the history of humanity that, despite being based on rigorous philological and documentary research, are also remolded by the artist with highly idiosyncratic results, in which temporal, spatial and epistemic planes merge together.

The exhibition – conceived by Andrea Bellini and organized by the Centre d’Art Contemporain, Geneva (February 22-April 30, 2017) in collaboration with Madre, Naples (May 27-September 18, 2017) and Koelnischer Kunstverein, Cologne (October 14-December 17, 2017) – includes about 70 works which span the twenty years of the artist’s career from 1996 to 2016, documenting and analyzing its various aspects.

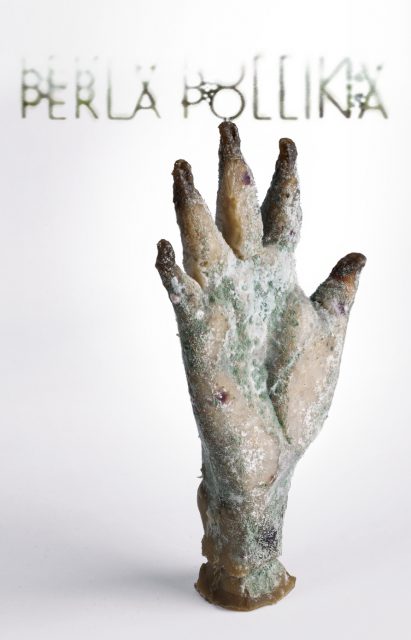

Right from its nonsensical title (generated by chance due to the erroneous effects of an auto-correct program), PERLA POLLINA, 1996-2016 presents itself as an exploration of the inventive and productive dynamics adopted by the artist. They are marked by an ascetic obsessiveness, the immensity of “allout” research strategies. In the pursuit of a result verging on the impossible, not knowing when to stop becomes the prerequisite for inventing new formats of experience, behavior and knowledge, and therefore for the creation of works in which theses research strategies are taken to the limits of recognisability of the components themselves or of the processes by which they are conceived and created. Renowned for his legendary transformation at the age of 25 into a man of 67 years old, Cuoghi uses his body not as an element of performance but as a preliminary vector for the works he is going to make. The importance of anthropotechnic processes of preparation, organization and research, just as the perpetual experimentation, the processual learning, the systematic breaking of pre-defined rules and codes would remain constants of a radically selftaught artistic practice. He experiments with materials and techniques, invents original solutions and examines unusual methodologies capable of taking on and coping with the highest level of indeterminacy possible, since it is essentially based on the rejection of a method. A nihilistic yet impassioned “doing without knowing how”, in which each work is like the last, or the first.

An example is Il Coccodeista (1997), a series of works on paper based on the artist’s decision to spend days wearing glasses whose lenses had been replaced with Schmidt-Pechan prisms which invert and overturn vision, transforming the perspective of surrounding reality and thus the possibility of recording it. Or the diary-works related to his experience letting his nails grow for 11 months so that he could not perform even the simplest functions, such as writing, while altering his tactile perception of the surrounding world. Or like the series of Asincroni (“Asyncronies”, 2003-04) and “black paintings” (2004-06). In the first series the artist intervenes on both sides of the overlapping sheets of transparent triacetate, preserving each mistake or change in order to create authentic palimpsests, similar to geological sedimentation, of a long, elaborate process from which dark, romantic characters, or deformed, spectral figures emerge.

In the second series, the intervention takes place on superimposed surfaces of glass used as a database in which the artist, operating like an alchemist, tries to control the reactions of the individual components to achieve a result that coincides with the empirical process of its own creation. The process is similar to the one used for his “maps“, in which the artist experiments with the relationship between coloring and corrosion with effects that fluctuate between transparency, opaqueness, superimposition and laceration which produce a planet immersed in a slow but inexorable drift in time and space.

The artist reflects as well on the interpretative vacuum created between the image we have of ourselves and the image that others have, like the vacuum between what we are and what we could have become in taking different decisions. Impatient with the interpretations of his work made by the art system, Cuoghi undertakes in this way a series of Autoritratti (“Self-portraits”) that restore the potential variations of his own personality among numerous possible incarnations: a young gangster, a spoilt child, a pretentious intellectual, the portly middle-age founder of the Dannemann cigar factory. Cuoghi’s skepticism of the art system, indeed his aversion to it, is also manifested in a series of Ritratti (“Portraits”) of artists, critics, curators or collectors (the latter ones done on commission) who the artist portrays, with an irreverent punk spirit, covered in wounds, bruises, mutilations or even with a severed head or as putrefied bodies half-buried in the earth, eventually becoming unrecognisable.

One of these portraits is of the Greek collector Dakis Joannou, painted like a renaissance bas-relief, a fifteenth century stiacciato in which the artist, juxtaposing different eras and styles, uses a highly personal mixture of pigments, modelling clay, wax, small objects and human hair, which he then photographs, achieving a surprising and almost unique result in the history of portraiture: the image is photorealistic but drenched in mystery – in a dystopian mixture of good and evil. It portrays a generous patron of the arts devoured by strange three-dimensional desires, alongside which the artist places reproductions of surgical instruments that have been dipped in batter and fried, which call to mind the text Il Tumore Liberato (“Tumour Set Free”), in which Cuoghi describes cancer, errors, accidents and exceptions as key elements in human evolution.

Following careful study of the Assyrian language and rituals, the artist has made, since 2008, a series of reproductions in an average-sized or large format of a small statue-talisman portraying the god-demon Pazuzu in which Cuoghi explores the potential of each element used, comprising not just traditional materials such as wood and stone, but also resins, adhesives, solvents and even worms and bacteria. Similarly, in the sound installations Šuillakku (2008) and Šuillakku Corral (2014) – which, together with Mbube (2005) and Mei Gui (2006) form a veritable “rhapsody of injustice” – Cuoghi manages to recreate a possible liturgical song of collective lament and affliction of the entire Assyrian people as they abandon the city of Nineveh. Not only does he offer a possible reconstruction of ancient Assyrian music, which is completely unknown to us, but also he performs each single sound and reconstructs in his studio each single musical instrument employed, based on scrupulous iconographic research and careful discussions with experts. These works will be the subject of a seminar arranged by Madre, in conjunction with the Conservatoire of Music of San Pietro a Majella, and organized during the exhibition. Among his most recent sculptural projects, based on a similar almost-performative preparation, Cuoghi combines sophisticated 3D technology with traditional firing techniques to create an invasion of ceramic crabs on the Greek Island of Hydra, where this animal has long been extinct (Putiferio, 2016, of which a large selection of documentary videos is screened in the video gallery on the ground floor).

The exhibition presents and interconnects, for the first time, the main cycles of the artist’s works. They are interpreted almost as if they were independent universes, obscure and feverish systems that apply only to themselves, like a language that, paradoxically, was spoken by only one person in the world. As the critic and curator Anthony Huberman writes in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition: “A radical thinker, Roberto Cuoghi constantly chooses the uphill battles. In the face of Western culture’s preference for the beautiful and the flawless, he chooses the mutilated and the deformed; in the face of the art industry’s fascination with the new, he chooses the out-of-date; in the face of our respect for those who have survived, he chooses to celebrate those who have gone extinct.”

The exhibition will be accompanied by the first retrospective monograph devoted to the artist (Hatje Cantz, international edition in English). The catalogue, which is about 500 pages and has numerous color illustrations, will include unpublished essays by Andrea Bellini, curator of the exhibition in Geneva (and, with Andrea Viliani, co-curator of the exhibition in Naples), and texts by Andrea Cortelessa, Anthony Huberman, Charlotte Laubard and Yorgos Tzirtzilakis, and an interview between the artist and Andrea Viliani, as well as a complete bibliography and chronology.

Roberto Cuoghi (Modena, 1973; lives and works in Milan), studied at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan, where he moved and where he now lives and works. One of three artists who will represent Italy at the forthcoming 57th Venice Biennale, Cuoghi was a winner in 2009 of the special mention Tradurre Mondi at the 53rd Venice Biennale and received as well a special mention in 2013 at the 55th Venice Biennale. He has also taken part in some of the most important periodically held international exhibitions – together with the Venice Biennale – such as Manifesta 4 in Frankfurt (2002), the IX Baltic Triennial of International Art, Vilnius and La sindrome di Pantagruel. T1-Torino Triennale (2005), Of Mice and Men. 4th Berlin Biennial (2006), 10000 Lives. Gwangju Biennale, Gwangju (2010). Solo shows devoted to the artist have already been held at national and international museums, such as: DESTE Foundation, Athens (2016); Aspen Art Museum (2015); Le Consortium, Dijon (2014-2015); New Museum, New York (2014); UCLA-Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2011); ICA-Institute for Contemporary Art, London and Castello di Rivoli-Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Turin (2008); Centre International d’Art et du Paysage de l’Île de Vassivière (2007); GAMeC, Bergamo (2003); GAM, Bologna (1997).